Focusing on product features leaves consumers’ emotional and social needs unexplored. This approach doesn’t uncover what Job they want to accomplish or the reasons why they buy.

Folk working in food, drink, motors, etc, all know that their primary aim is shelf defense: keeping retailers engaged, consumers happy, and teams confident their diversification keeps them a household brand.

More often than not, one or two products will make up the majority of your revenue. New products, product extensions and even new categories tend to result in flat launches or failure to move the needle.

How can innovation teams from the consumer packaged goods sector learn truly about what drives customer demand?

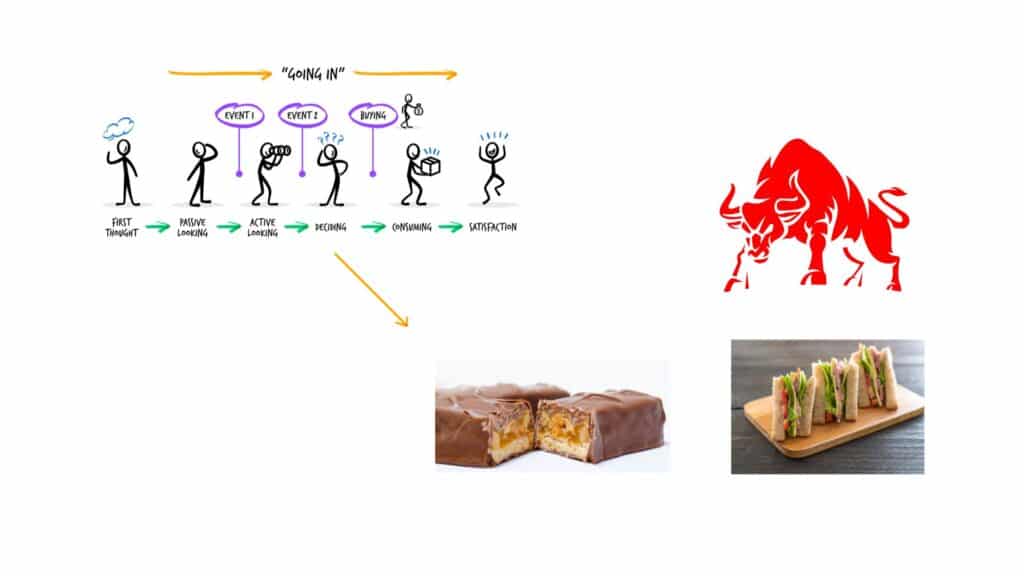

Let’s look at how Snickers and Milky Way compete against each other. (Spoiler… they don’t!)

What’s the difference between these two confectionary items?

On the surface, these two products appear to be similar. They’re both candy bars that are made in the same plant with chocolatey ingredients, and they sit side by side in the candy aisle.

When viewed from the supply-side, they seem to compete with one another.

But if we’re looking at this through the lens of shelf defence – why would someone pick a Snickers over a Milky Way?

As it turns out, the who, what, when, where, and why for each product are very different. (If you’re new to this, check out how Jobs supplements traditional research).

The context in which people buy a Snickers versus a Milky Way is completely different. And understanding this context has profound ramifications for whether or not a product succeeds.

The case for Snickers:

Think back to when you last bought a Snickers.

Why did you buy it? Chances are, it’s because you were hungry, you missed a meal, you were running out of energy…. you had lots to do. In other words, you needed a boost.

Snickers fits this situation quite well because it ‘feels’ like food; the nougat, caramel, and peanuts form a ball when you chew it, and you swallow it like food. As the Snickers hits your stomach, the growling and hunger stops because that ball absorbs the acid in the stomach and gives the body the energy it needs.

Snickers competes with a cup of coffee, an energy drink, or a sandwich.

The case for Milky Way:

Let’s look at a Milky Way. When you eat one, it converts into almost a liquid within three chews and slides down your throat, coating your mouth with chocolate and endorphins. It can take as long as 20 minutes to eat, and you savor the experience; it’s a candy bar.

Milky Way competes with ice cream, brownies, and a glass of wine.

Milky Way is a treat, Snickers is fuel.

They struggling moment they solve is different.

Snickers and Milky Way are fundamentally different in terms of the struggling moment that they solve, and the context they are consumed.

They are different in terms of the demand that they fulfill.

What it meant for Snickers

Understanding this dynamic was big for Snickers. Once they uncovered the demand and began marketing to people in their struggling moment, sales skyrocketed. In fact, it’s the bestselling candy bar in its category with over $4 billion in sales.

Once they uncovered the demand and began marketing to people in their struggling moment, sales skyrocketed.

Supply Versus Demand

To uncover demand, you must understand way more than who your customer is. What’s causing them to make a purchase? It’s understanding value from the customer-side of the world as opposed to the product-side of the world. It’s about realizing the progress that people are trying to make based on their context.

Your product is merely part of their solution.

Many organisations will build a customer profile using a persona. That’s not a good idea, as I share with you in my article, JTBD versus personas.

You need to think about your consumer as nebulous. An imagined, personified version — an aggregated set of demographic and psychographic information. You aggregate and triangulate the consumer around the product through correlative data. You think of your creation in terms of competitive sets within a category or industry.

If Mars, Inc. had viewed Snickers from the supply-side, they would have focused on Milky Way as the competition.

They would have zeroed in on making Snickers more delicious — taste-testing Milky Way and Snickers side by side, comparing ingredients, and tweaking the contents.

In the end, they would have had two candy bars that were a parody of each other, missing a $4 billion opportunity.

Focus on the Demand Side

When you innovate from the demand side, you realize that the customer has a completely different perspective. They usually have a completely different reference point of your product. Think about the Snickers vs energy drink instead of Snickers vs Milky Way.

Their context revolves around the new desired outcomes they seek, and their competitive sets aren’t actually competitive sets but candidate sets: “I can do this, or I can do that.”

The customer has no idea how Snickers bars are made, and they don’t care! In most cases, they can’t tell you that a Snickers would even solve their struggling moment until they’ve tried it or until you step in to let them know.

In my experience, most innovators and entrepreneurs are more focused and skilled at the supply-side. It’s critical that you understand how demand works.

How does your product or service fit into people’s lives?